- Details

- Written by Dr. Clint Moroziuk

- Category: Education Philosophy

Catholic schools in Alberta have a distinct mission; providing an education within the framework of the provincial curriculum, and doing so in an atmosphere that is permeated by faith. The role of the principal as a leader of faith within the school community is essential in fulfilling this mission, as they are responsible for overseeing teaching and learning, while at the same time nurturing the spiritual growth of students, staff, and the broader school community. My doctoral research focused on the role of the principal as faith leader within Alberta’s Catholic schools. In this brief article, I will attempt to delve into the importance of this role and identify a few key competencies and responsibilities of principals in Catholic schools.

Perhaps the most fundamental aspect of the principal's role as a faith leader is the promotion of Catholic teachings and values throughout the school. This involves not only ensuring that Catholic doctrines are integrated into the curriculum, but also that they are incorporated into the daily life of the school. This can include the use of prayers and religious observances in school events, the promotion of community service and social justice initiatives, and the encouragement and support of faith-based extracurricular activities.

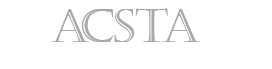

Another important responsibility of the principal as a faith leader is the cultivation of a strong Catholic culture and identity within the school. This includes creating an environment that is welcoming and inclusive to students, staff, and families of all backgrounds, while also celebrating the unique aspects of Catholicism. It also involves modeling and encouraging behavior that is consistent with Catholic values, such as kindness, respect, and compassion. Convey (2012) proposes a fairly structured model regarding the key components of Catholic identity which illustrates the basic components of both content and culture:

According to Convey (2012), some of the most important elements of Catholic school identity include a strong faith community, the teacher of religion being Catholic, starting the day with prayer, and Catholic teachings being presented in religious education courses, but also integrated into the general curriculum to the greatest extent possible. As not only a faith leader, but also the instructional leader in the school, it is the responsibility of the principal to oversee all aspects of Catholic identity and culture, from religious instruction to faith activities, liturgies, and service projects.

In order to fulfill these responsibilities, the principal must possess a deep understanding of Catholic teachings and their relevance to modern society. This requires ongoing professional and faith development, as well as a willingness to engage in theological reflection and dialogue with others in the school community. Additionally, Catholic school principals are called to model Catholic values and teachings in their own life. This involves living out the faith in their personal and professional life and being a visible and authentic example of faith for the school community.

In addition to promoting Catholic teachings and values within the school, the principal as a faith leader must also work to build strong relationships with the broader Catholic community. This can involve collaborating with the local parishes, diocese or eparchy, and other Catholic organizations (i.e., Catholic Social Services, Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, etc.) to promote shared goals and initiatives. It also involves being an active participant in diocesan or eparchial events and initiatives, and fostering a sense of connection between the school and the wider Catholic community.

With so much good news to share, the principal as a faith leader must be able to effectively communicate the school's Catholic identity to stakeholders both within and outside of the school. This requires the development of clear and compelling messaging that conveys the school's mission and values, as well as the successes and challenges of the school's faith-based initiatives. It also involves actively engaging with the media and other external stakeholders to promote the school's Catholic identity and achievements. This requires leadership and guidance at the division level, regardless of whether or not there exists a dedicated communications individual or department, to ensure that communication meets a basic standard and aligns with the mission and vision of the school jurisdiction.

The principal's role as a faith leader in Alberta's Catholic schools is a complex one that requires a broad range of skills and expertise. By promoting Catholic teachings and values, cultivating a strong Catholic culture within the school, building relationships with the broader Catholic community, and effectively communicating the school's Catholic identity to stakeholders, the principal as a faith leader plays a critical role in shaping the faith and character of the school community. What’s more, is that this must all be accomplished while attending to all other elements of leadership in the school, as articulated in both the Alberta Education Leadership Quality Standard (LQS) and its Catholic sister document, the Council of Catholic School Superintendents of Alberta (CCSSA) Catholic Leadership Standard, which adds to the LQS the component of Embodying Catholic Leadership and permeates faith through all other aspects of school leadership. The interconnectedness of all aspects of leadership is depicted in the below graphic, which was adapted from a similarly-styled graphic developed by the College of Alberta School Superintendents.

In conclusion, the role of the principal as a faith leader in Alberta's Catholic schools is multifaceted and essential to fostering a strong Catholic identity within the school community. Through integrating Catholic teachings into the curriculum, actively engaging the school community in the faith, promoting service to the community, working closely with clergy, families, and Catholic agencies, and modeling Catholic values and teachings, the principal is able to create a Catholic learning environment that inspires students and staff to live out their faith in their personal and professional lives. To generalize, the faith leadership role of the Catholic school principal can be defined as living gospel values and serving as a Catholic role model to the school community while working to permeate faith into all aspects of the work of school management and leadership. Sounds simple enough.

References

Convey, J. J. (2012). Perceptions of Catholic identity: Views of Catholic school administrators and teachers. Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice, 16(1), 187-214. doi:10.15365/joce.1601102013

Council of Catholic School Superintendents of Alberta. (2019). CCSSA Catholic leadership quality standard competency braid [Graphic].

Dr. Clint Moroziuk has worked in Catholic education for the past 26 years and has served as the Chief Superintendent of Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools since 2020. He holds a Bachelor of Education from the University of Alberta, a Master of Arts in Education from the University of Phoenix, a Master of Religious Education from Newman Theological College, and a Doctor of Education from the University of Calgary. He recently collaborated on designing a course for the Master of Education program at St. Mary’s University in Calgary and looks forward to serving as an instructor in that program in the future.

- Details

- Written by Brett Fawcett

- Category: Education Philosophy

The Three Forms of Permeation

Previously on this blog, I reflected about what it means to say that Catholic schools should be characterized by permeation. (Some, with good reason, prefer the word “integration,” and, if you are one of these people, you can feel free to mentally replace “permeation” with “integration” every time it appears in this post.) I suggested that there are three forms of permeation: Worldview permeation, worship permeation, and witness permeation.

Since writing that post, it has occurred to me that these three forms of permeation roughly correspond to the three offices of Jesus Christ: Prophet, Priest, and King.

- The prophet’s mission was to preach the law of God, to explain to the people of God what that law called on them to do in every aspect of their lives, and to remind them of God’s promises. This corresponds to worldview permeation.

- The priest’s function was to make the sacrificial offerings to God and to officiate over the people’s liturgical celebrations. This corresponds to worship permeation.

- The king’s job was to rule the people in accordance with God’s laws and to execute justice, especially on behalf of the poor and downtrodden. This corresponds to witness permeation.

Jesus fulfills all these roles, and permeation is therefore a participation in the ministry of Jesus Christ as applied to the work of education. (This should remind us that permeation is also impossible unless it occurs through Jesus Christ, Who has sent His Spirit to empower us to carry on His mission.)

But the question then arises of who is supposed to do this work. The Magisterium (that is to say, the Church exercising her authority to teach) has consistently stated that the task of permeation in a school falls primarily to its teachers–not to administrators, trustees, parents, students, or support staff (though every one of these groups has an important role to play as well), but to the teachers. Having solid Catholic teachers may not be a sufficient condition for a permeated school (for example, you could have a school full of great Catholic teachers who are stifled by bad policies), but it is a necessary one.

What Kind of Teachers?

The Catholic School Superintendents of Alberta (CCSSA) has recognized this and have produced excellent criteria for identifying the kind of teacher a school needs if permeation is going to take place there. (Remember, permeation is the work of the Holy Spirit, not us, but God works through instruments, and so a principal will want to hire teachers who are able and willing to serve as His instruments.)

One such metric is the Catholic version of the Teaching Quality Standard (TQS), which takes the provincial standards for teacher professionalism and adds various indicators that are particular to Catholic education. For example, the TQS used by public schools lists “Engaging in Career-Long Learning” as a competency teachers should strive for. In addition to the indicators listed in that version, the Catholic TQS includes “[s]eeking personally to grow in his or her spirituality and faith, understanding of Catholic teachings and doctrine” as one of the signs of this competency.

This is helpful, but it is worth remembering that the TQS is a secular set of criteria onto which the Catholic TQS imposes a distinctively Catholic perspective. This is fine, as far as it goes, but one wonders if there is not a criteria for Catholic teachers that starts with the question, “What kind of teacher can God use for permeation?”

One possibility here is found in a helpful CCSSA document called “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” To tease out the criteria for such a teacher, this text essentially works backwards from Archbishop Miller’s five marks of a Catholic school, that is: A Catholic school is (1) grounded in a Christian anthropology, (2) imbued with a Catholic worldview, (3) animated by a faith-infused curriculum, (4) sustained by Gospel witness, and (5) shaped by a spirituality of communion. Based on these, the CCSSA document identifies the “five marks of an excellent Catholic teacher”:

- “An excellent Catholic teacher recognizes that each person has an eternal destiny and is created in the image of God.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher expresses and develops a living Catholic vision of the world.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher permeates faith and wisdom through pedagogy and curricular content.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher witnesses to others a life lived in relationship with Jesus Christ.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher contributes to a spirituality of communion.”

This is undoubtedly a great list of things a Catholic teacher should do. After all, these are marks of an excellent Catholic teacher. By definition, a mark is something that is visible; it sets what is marked apart for the observer. An alert administrator should be able to observe an excellent Catholic teacher doing all of these things.

At this point, however, the philosophy teacher in me rears his punctilious little head and fussily insists on making two observations.

One of these observations is that there is such a thing as the fallacy of division. This is the logical mistake of assuming that, because something is true of a whole, it must be true of each of the parts of that whole. An example of this fallacy expressed in syllogistic form would be:

- A car is capable of self-propulsion.

- A steering wheel is part of a car.

- Therefore, a steering wheel is capable of self-propulsion.

Obviously, this is an error. The steering wheel, like all the other parts of the car, has a specific function; when all the parts are performing those functions correctly, then the whole car has the power of self-propulsion. This is the principle of emergence: Powers and properties that are not present in the individual parts emerge when they come together as a whole. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” as they say.

I worry that we may be committing the fallacy of division if we reason thusly:

- A permeated Catholic school has five particular marks.

- Teachers are part of permeated Catholic schools.

- Therefore, each teacher will also have those five particular marks.

To put this differently, what makes sense when describing a whole school can be a bit puzzling when applied to a particular teacher. It makes sense to say a school, as an institution, should recognize the supernatural dignity of each student as well as be animated by a faith-based curriculum. On the other hand, for an individual, isn’t recognizing that each person is made in God’s image (the first mark) just an extension of having a living Catholic vision of the world (the second mark)?

In the same vein, couldn’t there be qualities an individual Catholic teacher must possess (such as classroom engagement skills) that can’t be predicated of the whole school? If so, then using the five marks, which apply to the entire institution, to understand the work of a single teacher runs the risk of leaving out qualities which are distinct to a teacher’s work. It is interesting that “The Excellent Catholic Teacher” includes an appendix on the Catholic teacher’s spiritual commitments and pedagogical style, perhaps indicating that the five marks do not adequately cover all the characteristics we should expect to find in a Catholic teacher.

The other observation comes from the Catholic philosophical tradition. As mentioned, these five marks refer to what a Catholic teacher does. But where does that doing come from? The medieval Scholastics, when working out their Christian philosophy of the universe, formulated a rule: operari sequitur esse. Roughly translated, this means that “the actions of a being flow from the nature of that being.” A teacher can only do the kind of actions described in the five marks if they already are a certain kind of person.

To put this another way: You can’t just ask any given teacher to be able to do all these things. A teacher who lacks certain personal and professional qualities won’t be able to permeate faith and wisdom or witness to a life lived in relationship with Jesus Christ, just like a teacher without certain personal traits won’t be able to work in a Suzuki music school or a hockey academy. (Notice: Even if a teacher were a good educator and a fan of hockey, that wouldn’t mean he was suited to teach at a hockey academy. By extension, is a teacher ready for permeation just because she is a good teacher and a devout Catholic?) Before looking at whether a Catholic teacher does these things, we should consider what kind of teachers can do these things.

To that end, I would suggest that, beyond the marks of a Catholic teacher, we should be on the lookout for teachers with certain kinds of traits, personal characteristics that give rise to the actions from which a permeated school emerges.

The Five Traits of a Catholic Teacher

The Church’s Code of Canon Law lays down certain rules about who should be allowed to teach in Catholic schools. Canon 804 §2 declares that religious educators (which really means all teachers in a Catholic school, since all education in a Catholic school has a religious dimension) “are outstanding in correct doctrine, the witness of a Christian life, and teaching skill.” The 1982 Vatican document Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith add two further criteria: Catholic teachers should be able to work in community, which means collaborating with colleagues as well as with parents (para. 34) and “develop in themselves, and cultivate in their students, a keen social awareness and a profound sense of civic and political responsibility” (para. 19).

From these Church documents, then, we gather that a Catholic teacher must possess at least five traits:

- Knowledge of Catholicism

- Christian witness in life

- Pedagogical knowledge

- Skill in collaboration

- Sense of civic responsibility and need to instill this in students

There are two groups of traits here. The first two are unique to Catholic teachers. The last three can also be seen among non-Catholic teachers, but will look different in a Catholic teacher. I call these Permeation-Unique Teacher Traits and Permeation-Infused Teacher Traits, or PUTTs and PITTs. (Of course, you could also call them IUTTs and IITTs.) The PUTTs inform the other three traits and turn them into PITTs.

All teachers should be skilled in pedagogical technique. However, two equally skilled teachers could have two completely different pedagogical strategies. This matters because different pedagogical methods have different philosophies embedded in them, and some of those philosophies are more compatible than others with the Catholic view of reality. To take just one example: In the realm of early childhood education, compare the pure constructivism of the Reggio Emilia method, which developed in non-Catholic schools, to the emphasis on structured play-based learning in a Montessori classroom. This difference is not unrelated to the fact that Maria Montessori was a devout Catholic and therefore had a belief in objective truth that may not be present in the Reggio pedagogical philosophy. This does not mean a Catholic teacher in an early learning classroom must strictly follow Montessori and learn nothing from Reggio, but it does mean she will be aware of whether her pedagogy is in accordance with the Catholic worldview. This third trait is therefore to be understood through the lens of the first trait.

All teachers should have skills in collaboration, but, for a Catholic teacher, this is part of a broader “spirituality of communion,” to go back to the phrase of “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” For her, this will be both an exercise in professionalism as well as a recognition that the work of Catholic education is always ecclesial (that is to say, rooted in the broader community of the Church). The Catholic teacher recognizes that she is part of the body of Christ and plays an important but subservient role in a bigger plan that God is working out in her school community. In collaborating – which often takes great humility – the Catholic teacher testifies by her actions that permeation is ultimately God’s work, not hers. The second trait therefore shapes this fourth one.

All teachers should have skills in collaboration, but, for a Catholic teacher, this is part of a broader “spirituality of communion,” to go back to the phrase of “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” For her, this will be both an exercise in professionalism as well as a recognition that the work of Catholic education is always ecclesial (that is to say, rooted in the broader community of the Church). The Catholic teacher recognizes that she is part of the body of Christ and plays an important but subservient role in a bigger plan that God is working out in her school community. In collaborating – which often takes great humility – the Catholic teacher testifies by her actions that permeation is ultimately God’s work, not hers. The second trait therefore shapes this fourth one.

Finally, all teachers should be concerned for social justice, but what exactly – for a Catholic teacher – social justice looks like, and how to bring it about, is defined by Catholic Social Teaching as outlined in the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. Her vision of what is wrong with politics and the economy, and the steps we need to take to address those problems, will therefore look (at least a little different) than it does for her counterpart in a secular school. To wit: the secular teacher may not see a connection between contraception and climate change – both symptoms of what Pope Francis calls “the throwaway culture” (para. 22 of Laudato Si) – or between prayer and social activism; a Catholic teacher, however, will perceive these connections and model the inseparability of love for God and love for neighbour to her students. Both the first and the second traits are at play in this fifth one.

A teacher who possesses these five traits, or who is being formed in them and allowing God to develop them in her, is ready to participate in Christ’s prophetic, priestly, and kingly ministry in her work. A school staffed with teachers like her is one where permeation will emerge and the five marks will be visible for all to see.

Brett Fawcett teaches for Elk Island Catholic Schools at the Chesterton Academy of St. Isidore, and is a doctoral student at the University of Calgary.

- Details

- Written by Eugenia Pagnotta-Kowalczyk

- Category: Education Philosophy

In October of 2021, Pope Francis announced to the world, that the Church would undertake the enormous task of consulting with the laity of every diocese and archdiocese in the world. Thus the Synod on Synodality began its journey.

The Holy Father asked:

- How is this “journeying together” happening today in your local Church?

- What steps does the Spirit invite us to take in order to grow in our “journeying together”?

These two questions strike at the core of our Catholic identity. We are being asked to examine our self in relation to the church and how we can grow the mission of Christ – individually and in communion with one another.

The reason Catholic schools exist is to bring Christ to our students through the message of the Gospel. Through the teachings of the Church, witness of the faith community, and support of the Catholic school, the triad of HOME, SCHOOL, and PARISH is well established.

We know this. However, the challenge we face is real – how are we doing this in relationship with one another and in full communion with the Catholic Church? At every turn we watch a secular culture preaching individualism to our children. We hide under the bushel basket, afraid of being attacked by what is less than a tolerant society. Yet, without the preaching of the Gospel (in all places, on all occasions, without hesitation, reluctance or fear), we fail.

During the Synod Listening Session we shared our vulnerabilities as teachers, students, parents, administrators, politicians, and community members. When we began to really listen to one another with the intent to understand (versus our predisposition to merely 'respond'), we embarked on a journey of discovery. We felt the passion, joy, and at times despair of Catholic education. Many express that Catholic schools play a tug of war with our secular society; that when these tensions emerge they play havoc with our Catholic identity and we lose sight of who we are. This sampling of comments from the Synod Listening Sessions provide a lens through which we may begin to discern. I share their unedited voice, to respect both their message and their emotion:

- Other teachers and staff at the Catholic School where I work and in other Catholic schools. We are called to be authentic with one another, sharing more deeply our joys, sufferings, passions and doubts

- My biggest challenge is feeling safe to talk about my faith in the school staff room as many in it, although Catholic, vocally admit to not being interested. These are the people who are supposed to be teaching the faith in Catholic schools.

- When I hear the word church I think of a community of people being brought together by faith. I think of new begins and change. When you go to church you are impacted by the lessons and story's they tell whether they are good or bad.

- For a lot of students we do a lot of social justice work, I didn’t make an automatic connection between our acts of service and the work of the Church. I understood the act of kindness as something random, rather than an active expression of my faith

- In a school, the principal plays a key role in influencing the climate within that school and it’s Catholicity; likewise, the parish priest must have a passion for his work and a genuine love for young people.

Similarly, in the AWCB and CCCB Synod synthesis report, the following comments were expressed:

- Improve the faith formation in Catholic schools, strengthen the connection between schools and parishes, and support school teachers in living their faith

- There is a need to develop ongoing catechesis and education and to find new ways to engage families. It was also pointed out that parishes and, where they exist, Catholic schools, need to be more active in sacramental preparation so as to inspire Catholics

- Concern with regards to the ongoing challenge of secularization in Catholic schools

We now eagerly await to learn about the themes generated during the Continental Listening Sessions. It is from here that the Instrumentum Laboris will be written in preparation for the XVI General Ordinary Assembly of the Synod of Bishops in Rome.

It cannot be overstated that our Catholic schools need to be steeped in authentic teaching of the faith with well-formed teachers, administrators, and leaders. School, family, and Church must continue to forge paths that allow everyone to journey together, always in alignment with the teaching of our faith.

May our Synodal journey continue to inspire us to speak and listen with kindness and compassion for the purpose of cultivating a Catholic culture and identity in our Catholic schools. Our students deserve nothing less.

Dr. Eugenia Pagnotta-Kowalczyk is a former teacher and principal in the Edmonton Catholic School Division, as well as Executive Director and Director of Advocacy of the Alberta Catholic School Trustees' Association. She has also worked as a sessional instructor at St. Joseph College at the University of Alberta. She holds a PhD in education leadership and Catholic identity from the University of Portland and an M.Ed. in curriculum and leadership from the University of Alberta. She is currently employed at the Archdiocese of Edmonton as Mission Engagement Lead and Synod Coordinator.

- Details

- Written by Brett Fawcett

- Category: Education Philosophy

The reason why the Church teaches that Catholics should send their children to Catholic schools whenever possible, and the reason why Alberta’s constitution protects the right of Catholics to have their own separate schools, is because the purpose of Catholic education is to form young people in obedience to Christ and to show how Jesus is Lord over every corner of the universe. Achieving this goal requires having a school–one where everything about that school points students towards God. The word usually used to describe this is “permeation,” though some school authorities prefer “integration.”

However, despite how commonly “permeation” appears in magisterial documents and in school policy, finding a succinct, handy definition is surprisingly difficult. This leaves a couple of important questions open:

- What exactly are we permeating?

- What exactly are we permeating it with?

Take an English class that opens and closes with the Our Father. Is this permeation? Or take a Biology class where the teacher mentions that Gregor Mendel, the founder of genetics, was an Augustinian friar. Would this qualify as permeation? One is an example of school ethos being given a Catholic aspect; the other is a bit of instructional information which makes a Catholic connection. These are two different aspects of school life into which a Catholic component has been included, though one is spiritual and one is more cerebral. So, which is it? Is permeation about infusing Catholic spirituality into the atmosphere, or about infusing Catholic content into the study materials?

Or–to put it a bit differently–suppose these are both examples of permeation. We have mentioned that, in one sense, the purpose of having Catholic schools is permeation. If the teachers include these elements, have they permeated “enough”? How much prayer is “enough” to permeate? How many Catholic-relevant facts are “enough” to include in a lesson before it is sufficiently permeated?

These are important questions because, in our secular age, the Catholic school (and the Catholic university) may be the only major avenue for generating a Catholic culture, and is probably the most important location of Catholic evangelization. Not only is Catholic formation not coming in any great measure from entertainment, media, social organizations, or government, but, sadly, it is also largely absent from Catholic homes, leaving the school as perhaps the only opportunity for the next generation to learn how to love the Lord their God with its heart, soul, mind, and strength.

(We can perhaps take comfort in the fact that this is not the first time this has happened. In the fourth century, St. John Chrysostom complained that parents took care to train their children in arts and literature but completely neglected to bring them up in the faith, and the Catholic Encyclopedia notes that it was “no longer possible for children to obtain proper religious and moral training in their own homes” is what gave rise to the monastic schools, forerunners of the Catholic schools of today.)

This culture and this formation will only develop if permeation is achieved. Therefore, let’s pay close attention to how the Magisterium uses the word in its official documents on education.

What we find is that it seems to be used in two different senses.

One use of “permeation” uses it to refer to the intentional integration of Catholicism into classrooms and explicit instruction. Since this is what it meant in its first appearance in Church teaching (paragraph 80 of the 1929 encyclical Divini Illius Magistri), we can consider this the original and primary sense of what permeation is. It is also how Vancouver Archbishop Miller uses the word when he includes it in The Five Essential Marks of Catholic Schools as the fourth mark: “Imbued With a Catholic Worldview Throughout Its Curriculum.”

However, in most of the documents from the Congregation for Catholic Education, “permeation” refers to how the entire ethos, including the relationships between staff members, should exude a Christian spirit of, as Vatican II’s Declaration on Christian Education, Gravissimum Educationis, puts it, “freedom and charity”. Now, it is obviously true that a Christian school’s atmosphere should be permeated by a sense of Christian devotion and love. However, this is also true of a parish office, a Catholic soup kitchen, or even a business with Catholic employees. There doesn’t seem to be anything specifically educational about this kind of permeation.

Moreover, when it comes to what exactly we are permeating schools with, these references are still frankly a bit nebulous. What exactly does “piety” or “the Gospel spirit” look like in a school? Won’t this look different depending on what aspect of school life is being permeated?

I think it would be helpful if we first distinguished different forms of permeation. Paragraph 2 of Gravissimum Educationis can serve as our guide. It explains the nature of Christian education this way:

“A Christian education does not merely strive for the maturing of a human person as just now described, but has as its principal purpose this goal: that the baptized, while they are gradually introduced the knowledge of the mystery of salvation, become ever more aware of the gift of Faith they have received, and that they learn in addition how to worship God the Father in spirit and truth (cf. John 4:23) especially in liturgical action, and be conformed in their personal lives according to the new man created in justice and holiness of truth (Eph. 4:22-24); also that they develop into perfect manhood, to the mature measure of the fullness of Christ (cf. Eph. 4:13) and strive for the growth of the Mystical Body; moreover, that aware of their calling, they learn not only how to bear witness to the hope that is in them (cf. Peter 3:15) but also how to help in the Christian formation of the world that takes place when natural powers viewed in the full consideration of man redeemed by Christ contribute to the good of the whole society.” (emphasis added)

We could boil this down to three major goals; or, to use curricular language, outcomes. Students at Catholic schools should graduate with:

- A deeper knowledge of the Faith

- A deeper awareness of how to worship God

- A deeper understanding of how to live in a Christian way in society

With this as a framework, I would suggest we can recognize three different forms of permeation. For mnemonic purposes, these can be categorized with three words starting with the letter “w”: worldview permeation, worship permeation, and witness permeation.

- Worldview permeation could also be called theological permeation or intellectual permeation. This refers to teaching students how to think about the universe in a way that is informed by the revelation of Jesus Christ. The teachings of the Church have implications for how history, physical science, literature, and even mathematics are interpreted. If any subject is taught without reference to God, the implication is that God is irrelevant to that subject. On the other hand, an integrated Catholic worldview will have a perspective on evolution, on artificial intelligence, on different economic systems, and on every other topic in creation, all of which are logical deductions from the Creed. The Catholic intellectual tradition should shape our entire curriculum, and students should have an integrated and coherent worldview, rather than one which professes acceptance of Christian teaching alongside total inconsistent acceptance of secular views about sexuality and society or materialist views about cosmology. This obviously requires a robust intellectual formation of teachers, and perhaps the Catholic community needs to have a serious conversation about the kind of pre-service training Catholic teachers should receive.

- Worship permeation could also be called spirituality permeation or prayer permeation. The ultimate goal of Catholic schools, and of all Catholic activity, is to know and love God. It is more important to get into heaven than college. Although salvation is by God’s grace, Catholic schools have the task of forming students so that they are open to that grace by knowing how to speak to God and how to listen to God in the way that He has revealed to us that we should. This does not just mean prayers at the beginning of class, or school liturgies–although these are indispensable. It also means that the awe students experience when learning about the beautiful intricacies of the universe should blossom into praise of its Creator. It means the stress and suffering they experience in preparing for examinations should be offered up with Christ’s suffering on the Cross. It means that breathing exercises should not be a simple internal silence but a silence that waits for God’s Word; it should be more like centering prayer than Buddhist meditation. And, when students are struggling with making decisions, they should have been taught to ask God for His guidance and to discern His will carefully (and how). Again, this should be present in every class at a Catholic school, even if it means finding or writing opening and closing prayers for a lesson that are relevant to the curriculum (“thank you, God, for creating trees”).

- Witness permeation could also be called morality permeation or praxis permeation. This refers to teaching students to live out the ethical obligations of being in communion with God. If worldview permeation relates to knowing about God, and worship permeation relates to loving God, witness permeation relates to loving one’s neighbour. This relates to both personal and communal morality. Students should learn fortitude and self-control (physical education can play an important role here) in order to master concupiscence in cooperation with grace and should be trained to be responsible and proactive citizens who use the knowledge they received from science and social studies classes to implement Catholic Social Teaching in the world. (Again, there is no subject where the behaviour of the students will be completely irrelevant. The question, “What can students do with this information?” should always be lurking, and the answer should always be some variation on “they can use it to serve God and others.”)

When teachers ask, “Have I permeated enough?”, this could be a useful checklist for them: “Have I taught my students how to interpret this information in the light of the Faith?” “Have I used what I am teaching to direct my students towards God in prayer and worship?” “Have I taught my students how they can use this content in a moral and loving way?”

Do all three forms of permeation need to be present at all times? In all likelihood, not every lesson will necessarily lend itself to this. However, it’s worth noting that, if done correctly, each form of permeation should implicitly contain the other two. Good spiritual practices and just social action should teach students to have correct theology: Lex orandi, lex credendi (“the law of prayer is the law of faith”). On the other hand, correct theology, and the breathtaking impressive scope of the Catholic intellectual tradition, should inspire students to want to adore God and to love and serve others. Orthodoxy inspires orthopraxy.

So, if this is what we are permeating with, what exactly are we permeating? Are lessons being permeated, or is the whole ethos of the school being permeated? As I mentioned, the original definition of permeation was that it had to do with curriculum. I think this has to continue to be its primary meaning. However, as every teacher knows, there are at least two kinds of curriculum: The explicit curriculum and the implicit curriculum. The explicit curriculum is what is overtly taught, but the implicit curriculum is what is indirectly taught. It is the lessons and messages the school sends to students by the way it acts, by what it treats as being important, by its general “vibe.” If a Catholic school is permeated with a Gospel spirit of freedom and charity because its staff are imitating Christ in the way they work with each other, that is itself a lesson to the students at that school about what it means to be a Christian. In that sense, all five marks of a Catholic school are a form of permeation.

Therefore, I would propose a second way of distinguishing permeation: Explicit curriculum permeation and implicit curriculum permeation. This could be another kind of checklist for teachers: Not only, “What have I taught today in my instructional activities?,” but also, “What have I taught today by my actions?” In building relationships with my students, have I modeled Christ’s love that calls on us to care even for the most difficult lost sheep (as Dorothy Day put it, “I really only love God as much as I love the person I love the least”)? In dealing with my own frustrations, have I fallen back on prayer and forgiveness in a way that models Christlikeness? In my conversations with my colleagues (and are there ever any truly private conversations at a school), have my comments not only demonstrated Christian charity but also demonstrated intellectual consistency with the Church’s understanding of what is true about the world? (As we can see, the examination of conscience has great value as a tool of professional development.)

In summary, the answer to “What is permeation?” is that, on some level, it depends. There is permeation of the implicit curriculum and of the explicit curriculum, and both should be permeated with Catholic worldview, Catholic worship, and Catholic witness. Keeping this relatively simple heuristic in mind can hopefully help Catholic teachers, and the administrators who evaluate them, ensure that they are always showing their students how to take every thought captive to the obedience of Christ (2 Corinthians 10:5).

Brett Fawcett teaches for Elk Island Catholic Schools at the Chesterton Academy of St. Isidore and is a doctoral student at the University of Calgary.

- Details

- Written by Dean Sarnecki

- Category: Education Philosophy

Part I: Developing an Ecological Mindset for Catholic Education

As a teacher/chaplain in a Catholic high school, Earth Day was one of the few opportunities in the school year that I had to join the religious and spiritual teachings of the Church in a student driven movement, that was self-organized by them and engaged students in a meaningful manner that was not normally part of the organized spiritual life of the school. In ecology and environmental issues, the students and staff shared a common goal, vision, and values. This created an opening for the school staff to work with students; for Catholic teachings to address issues of faith and nature, spirituality, and ecology; and for the students to experience a convergence and collaboration of ideas between the secular and religious worldviews.

But are we forming teachers, both in-service and preservice, with the knowledge and the opportunity for spiritual and ecological conversion could greatly impact the students, families, and parish communities involved in Catholic education. As Catholic educational institutions, are we providing the knowledge and experiences necessary to make our schools, and teachers, ecological witnesses?

There’s been a growing recognition of the scale of modern environmental degradation, especially that caused by the climate crisis. Pope Francis has expressed concern about humanity’s failure to recognize the interconnectedness among the ecological and social challenges and the promotion of the common good. The Church has been a strong advocate of environmental and ecological issues for decades under the leadership of Popes Paul, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and now Francis. Church members, especially religious orders, male and female, have strongly protested environmental destruction and have offered a theology and spirituality of creation and relationship, including the fight for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the protection of their cultures and land.

Ecospirituality and the roots of the environmental movement grow deeply in the Catholic Church. Francis’s encyclical was one of many documents, teachings, and pronouncements by the Church on the integration of creation and humanity’s place within the world. Catholic schools and their teachers, as instruments of the Church and guided by CST, need to be formed in ecological awareness, informed of the issues and duties as citizens of the world, and personally transformed by ecological spirituality to become leaders in this movement. The call for environmental leadership and change is not new but is becoming increasingly louder and more urgent!

The final chapter of Pope Francis’ Laudato si’ directly addressed the role of ecospirituality, ecopedagogy, and religious education. The sixth chapter is vital to Catholic teachers, providing a means to enable teachers to incorporate climate change and environmental concerns in teaching, and infusing society with an environmental and ecological mindset. It is important that Catholic teachers understand the ecological movement, its complementary relationship to the teachings of the Church, and its power to spur dialogue in the public sphere.

Fr. Dermot Lane in his book “Catholic education in light of Vatican II and Laudato si” suggested that the final chapter of the encyclical relates three challenges that Catholic education faces in the 21st century (p. 47): (a) the encyclical’s critique of anthropocentrism, (b) the religious education challenge that the encyclical demands, and (c) the call for both an individual and a communal ecological conversion. I would like to touch on each of these three briefly.

1. Critique of Anthropocentrism

One of the encyclical’s central underlying themes is the need for a cultural change that embraces humanity’s common origin, mutual belonging, and a shared future with all creation. Francis suggested that, unless people modify and develop a new way of thinking about being human, no amount of education will change the current path, rendering education efforts ineffective. Francis declared, “There can be no ecology without an adequate anthropology” (para. 118). The encyclical uses strong language such as tyrannical (para. 68), distorted (para. 69), and misguided (paras. 118, 119, 122) to describe people’s anthropocentrism and the need for a change in anthropology.

Francis left no room for ambiguity. Going further than previous popes, he acknowledged that human beings cause climate change and that “once humanity declares independence from reality and behaves with absolute dominion”, creation will begin to crumble. Humanity must reorder itself—or decenter—and reconnect with the larger natural order. For Francis, this moment is both an anthropological and theological crisis, and humanity must attempt to reimagine its place within creation.

2. Educational Challenges provided by the Encyclical

Francis argues that education must address the lack of awareness of humanity’s common origins of creation, mutual belonging to each other, and the future that all creation needs to share.

Lane (2015) suggested that understanding the common origins of creation, beginning with cosmology and biological evolution, is necessary to contend with these issues. Religious education and teacher formation must help teachers and students recognize the place of human beings within the larger picture of creation. The fierce individualism and competitiveness of modern society contributes to the ecological devastation, especially the ubiquitous compulsive consumption found throughout the world.

Francis states the educational challenge includes going beyond exposing the “compulsive consumerism” of the free market economies of the globalized world, in which freedom is perceived as the freedom to consume and the failure to appreciate the reality that unlimited consumption is actually restrictive. Humanity has a responsibility to explore its relationship with objects and “things,” because people exploit and use nature in a destructive fashion. A world economy based on the unlimited consumption of finite resources creates and perpetuates an unhealthy relationship with the physical world: Francis quotes Pope Benedict “Purchasing is always a moral— and not simply economic—act”.

Pope Francis stated that the absence of humans’ self-awareness and self-reflection in the current ecological situation makes them incapable of offering guidance and direction. This absence becomes a source of anxiety that engenders feelings of instability and uncertainty, and the uncertainty can cause people to become even more “self-centered and self-enclosed”. Lane believed that we need a new vision of what it means to be human and regaining a sense of the place of humanity as part of creation is required.

3. A New Spirituality and Ecological Conversion

The last challenge is what the encyclical described as “the leap towards the transcendent which gives ecological ethics its deepest meaning”. Building on the work and thought of Pope John Paul II, Francis suggested, “So what they [those not committed to ecological change] all need is an ‘ecological conversion’”, whereby the effects of their encounter with Jesus Christ become evident in their relationship with the world around them. The Church has long taught that people need to live and create a “civilization of love” and expand it to a culture of care: “Care for nature is part of a lifestyle which includes the capacity for living together and communion. Jesus reminded us that we have God as our common Father and that this makes us brothers and sisters” (para. 228). The necessary love and respect are far beyond human relationships alone and include care for the environment and all creation.

The role of Catholic education in ecological conversion is essential. The encyclical called for two forms of conversion: a profound interior conversion and a conversion of the community. Central to this conversion is an encounter with Jesus Christ, which affects relationships with the created world. The task of conversion, difficult at the individual level, is the work of the community, with success possible only with a communal effort. Individual conversion requires the support of the community, and the community depends on the transformation of individuals.

Are our teachers and Catholic schools ready to lead this call to conversion? Do they have to be converted first? If so, how, and where?

Part II: Ecospirituality and Religious Education

Religious education curricula for Catholic schools are based on the goals of the Directory of Catechesis. The directory clearly states that, central to the education of youth in Catholic schools, themes “such as liberty, justice and peace and the protection of creation” are essential.

Canadian religious educator James Mulligan has referred to the notion of biasing the vision of Catholic education in schools. Social justice, including ecological and environmental concerns, should be a bias in Catholic schools. Catholic education must focus and form young people to understand the integral relationship among them, all living organisms, and all creation. This can only be achieved with teachers who themselves are formed and instructed in Catholic Social Teachings.

The pope’s call for ecological responsibility lies with each person and the institutions that form them, including the Catholic school and Catholic colleges that form teachers. He suggests that teachers need to reawaken the world, and their students, to the wonder and awe of the Earth so that they can truly encounter the universal connectedness and community that engages and sustains humanity. Teachers first must be awakened to reality before they can share this.

Educator and theologian Thomas Groome believed that Catholic schools play an integral role in leading students to an environmental consciousness:

"Pope Benedict XVI has been relentless in his call to unite ecological concerns with the Christian faith. This is as much a justice issue as a theological one. The practice of a “green” consciousness must be central to the Catholic school and formation of young people to preserve the environment and continue to recognize the sacramental nature of the Christian beliefs." (Groome, 2014, p. 216)

Catholic schools need to be justice-centered and committed to conservation, peace, and the environment. Social justice includes environmentalism and humanity’s relationship with all living things and the nonliving Earth. As sacramental communities, Catholic cosmology includes an awakening to people’s relationships with the biosphere, where God is revealed in the “awe, wonder and amazement” of creation and the diversity of life.

Education must also express the importance to youth and teachers of acting on environmentalism rather than just talking about it. Groome stressed that educators and strong curricula are crucial to an education that does justice: “If people come through a curriculum of Christian religious education and remain. . . negligent in their responsibilities. . . for the environment and ecology”, they have not been educated in Christianity.

Greening Catholic Teachers’ Formation

Groome wrote that a Catholic education should free the mind to search for truth; it should lead to the formation of students who live justly with a social conscience. He believed that every graduate from a Catholic school must leave with a commitment “to protecting the integrity of creation”. Unfortunately, CST are often seen as a secondary drivers in Catholic education curricula, including that found in many Catholic colleges; CST must be integrated more fully into the Catholic school and College and teacher formation in a tangible manner for a lasting impact. Witnesses are essential, and schools, governments, religious institutions all have a role to play. Developing teachers with the knowledge and skills to create initiatives that involve the environment and ecology, including human ecology, are important to the Church and society. These must be at the forefront of all Catholic education and teacher preparation.

Teachers’ formation in ecospirituality and environmental ethics, combined with the underlying anthropology that undergirds the Church’s position on creation and humanity’s place within, can potentially have two positive results. First, it can create a fresh new look at Christian teaching and facilitate a dialogue that impacts both the religious and nonreligious— both those who believe in the transcendent and those who live within an immanent frame. Second, in addressing the ecospiritual movement and the Catholic social justice tradition, a religious education in ecology can foster a common understanding or at least promote a more fully developed discussion of Christian anthropology and sacramentality.

In modern urban society, the natural world can be strange and distant. For sacramental churches, the division between humanity and creation has removed much of the innate symbolism of creation in sacramental rites. Yet, an ecologically centered perspective often sheds a different light on existence. God’s creation has nourished humanity and created a sense of kinship. Philosopher Charles Taylor explained that “we belong to the earth; it is our home. This sensibility is a powerful source of ecological consciousness”. Taylor also realized that at other times this alien and vast Earth can remind humans not only of their smallness, insignificance, and fragility, but also of the sense of mystery and enchantment.

The mission Catholic education is based in part on relationship, interconnectedness, and human ecology, I recommend that Catholic education place special emphasis on care for creation and ecospirituality in its curricula and teachers’ formation. Too often I have seen Laudato si’ and the pope’s messaging on care for creation reduced to a cliché: reuse, recycle, and reduce. While not discounting these actions, the reality is that Pope Francis’s and the Church’s teachings are much deeper and more powerful. Pope Francis wants humanity to reflect and renew its relationship with all creation intensely and profoundly. This broader viewpoint includes all human relationships.

Schools are ideal communities to form young people into universal citizens and at the same time instill within them faith and an ecospirituality. Teachers must be formed with the right balance of theology, science, and spirituality to recognize and interconnect with all aspects of creation. Pope Francis and the Church have provided a curriculum base and mission for Catholic education that enables Catholic educators to reach out to the secular community and begin a process of engagement and dialogue. Ecospirituality provides a language and a mission that the Christian community can use to engage and encounter the realities of global warming, climate change, rapid environmental change, and so on, and find connection, fullness, and human flourishing through this ecumenical issue.

Educational institutions, parishes, and Catholic schools need to educate all Christians, but especially teachers and other leaders in education, to the realities of CST and the work of the church in this field. This can only be accomplished through intentional efforts such as Courses, retreat programs, and professional development to sincerely understand and integrate CST and the message of care or creation, and Laudato si should be at the heart of these activities.

- Details

- Written by Matthew Hoven

- Category: Education Philosophy

Learning from publicly-funded Catholic schools elsewhere in the world can help our vision and planning in Alberta. We can find shared challenges and receive insight for future directions.

I was struck recently by a book chapter by a prominent Catholic educator, Dr. Michael Buchanan [1]. He's an Australian who has written extensively about religious education, and is well-connected to global research in Catholic education. His chapter includes two important insights: one historical and the other sociological.

First, Buchanan explains that Catholic schools in his home diocese of Victoria, Australia — which now contains some 400 Catholic schools — do not have enough teachers formed in the Catholic faith tradition. Historically, the problem first arose when governments were no longer willing to fund Catholic schools in the nineteenth century. The church brought in foreign religious brothers and sisters to lead the schools.

With the decline of religious vocations in the 1960s — and many religious communities expanding their places of ministry — lay people were once again needed in Catholic schools. Australia Catholic education went from rejecting to embracing lay teachers, and could better afford them with changes in public funding. Buchanan’s first insight, then, is that circumstances often change for the apostolate of Catholic schooling; leaders need to see challenges as new opportunities and not wait for others to solve their problems.

Second, Buchanan shares national survey findings about teachers in Australian Catholic schools. Eighty percent of primary teachers and 61% of secondary teachers identify as Catholic. Of these, 25% regularly go to worship services outside of the school — that's about 16% of all teachers.

Buchanan notes that despite what many would see as low church attendance figures for teachers, many of these educators are happy to work in Catholic schools and support their schools’ religious mission. In fact, teaching staff find the religious element even a significant part of their professional life as a teacher. This may seem odd to a church-going Catholic like myself, but educators find something of great value in Catholic schooling.

What do these historical and sociological findings from Australia mean for Alberta Catholic schools and its trustees? As an important level of governance in education, trustees have the responsibility to ensure Catholic schools are living out of their faith-based mission. Budgets are tight, but how can we get creative to provide substantial faith formation for teachers?

Buchanan points out that an Australian national body for Catholic education calls for faith formation that is systemic, ongoing, and accessible. When only small proportions of teachers practice their faith outside of school, school leadership needs to provide structured support for teachers. Well-resourced and accessible programming is needed.

He concludes that parishes should not be responsible for the faith formation of Catholic school teachers, just as they weren't when religious sisters and brothers were the main educators in Australian schools at the end of the nineteenth century.

Catholic educators elsewhere offer insight for us. They help us overcome isolation and fear in the face of our challenges, while potentially enabling us to re-frame our own perspectives.

Dr. Matt Hoven is an Associate Professor and Peter and Doris Kule Chair in Catholic Religious Education for St Joseph’s College at the University of Alberta.

Notes:

(1) Michael, T. Buchanan (2022). “Catholic Teacher Formation in the Land Down Under,” in L. Franchi and R. Rymarz (eds.), Formation of Teachers for Catholic Schools, pages 3-14. Springer.

- Details

- Written by Grant Gay

- Category: Education Philosophy

The need for faith formation for Catholic teachers is an ever-present reality. Modern Church documents – from the Second Vatican Council’s Gravissimum Educationis to the most recent instruction from the Congregation for Catholic Education, The Identity of the Catholic School for a Culture of Dialogue – point to the need for teachers to be well-formed in doctrine and Christian living. This requisite arises from the fact that, contrary to popular belief, Catholic schools are not for Catholics. Rather, the Church sees education as the foremost spiritual work of mercy, flowing from the Body of Christ, for the whole world. The Church instructs the ignorant as part of her Great Commission. Not just those ignorant of Catholic Christianity; this mercy is to be shown to those unfamiliar with mathematics, for instance, and the natural sciences, as well as those estranged from the humanities and fine arts. In speaking to the beauty, truth, and goodness of creation, the Church cannot avoid making reference to the Creator. Thus, education is primarily evangelical, and Catholic education is ‘Catholic’ because it is for everyone (the term ‘Catholic’ itself being derived from the Greek katholikos, or ‘universal’). In other words, it is not intended to be for Catholics, but rather from Catholics, and Catholic teachers need to be properly formed so that they are able to practice and teach Catholic Christianity.

This is no new concept, certainly, but just what should this formation look like? First, we have to acknowledge that teachers are generally drawn from the ranks of the baptized, few of whom are well-versed in their religion, and most of whom are trained as teachers at university programs that do not provide a sufficient amount of faith formation, if any. Referencing this fact is not intended to question the faith of our teachers, but rather acknowledge that the average Catholic does not know much about why they believe what they believe. We, the Church, quite obviously need to do a better job of adult catechesis in general, but I digress. It is, in part, up to Catholic school divisions to create professional development that aids in forming their teachers. These programs cannot be merely a requirement to attend Mass on Sundays (although that should be a part of them) and participate in parish life. Catholic school divisions need to have ongoing formation programs that address their needs as Catholic educational professionals, and not just Catholic adults.

Since Catholic teachers hold a lay leadership vocation in the Church, let’s take a look at the formation programs put in place for other Catholic leaders; our clergy. Seminary formation programs will often focus on four dimensions of formation: human, spiritual, intellectual, and pastoral. Each dimension focuses on a different aspect of the person to provide a holistic formation that enables effective ministry:

- Human formation celebrates what it means to be human; virtue, psychology, health, wellness, and a joy of life.

- Spiritual formation is that foundational practice of the faith; liturgy, sacraments, prayer, devotions, retreats, and the general practice of Catholicism.

- Intellectual formation focuses on understanding and articulating the beliefs held by the faithful; theology, philosophy, history, and other academic pursuits related to the faith.

- Pastoral formation provides the tools needed to guide those placed in one’s care; listening skills, counseling, behaviour, and learning those skills needed to lead people to God.

The teaching profession itself, as a secular entity, tends to address pastoral and human formation as teachers learn to care for and educate the youth. These simply need to be framed in the Catholic worldview as they continue to be addressed in professional development. With regard to spiritual formation, Catholic schools have an expectation – and provide plenty of opportunity for – practicing the faith with school liturgies, guest speakers, retreats, prayer, devotions, etc. Although all of these dimensions of formation need to continue throughout a teacher’s career, it is the area of intellectual formation that school divisions need to put a particular emphasis on.

An emphasis on intellectual formation is not to say that every teacher needs to have formal education in theology; rather, the emphasis arises from the nature of the teaching vocation. Learning is a knowledge-focused endeavour, and a teacher needs to know more about the subject matter than her students do in any subject she teaches. Further, the more a teacher knows about Catholic Christianity, the more he can permeate the faith into his subjects.

When Catholic educators hear the word 'permeation' we tend to think of the sacramental and often sentimental trappings of our Catholic schools. This list includes crucifixes over doors, cross-shaped windows, advent wreaths, saintly slogans stenciled on walls, rosaries, statuary, or bibles on shelves. We might include prayer and other religious practice on the list, which certainly set our schools apart as Catholic. We then proceed to instruct in a secular curriculum (barring formal religious education classes), with – ironically – nary a mention of our religion.

The whole concept of ‘faith permeation’ is that our faith has a lasting, changing effect on us. This isn’t an infusion, diffusion, or suffusion; such language implies an additive ‘pouring out’ of our faith into, throughout, or onto our schools. Rather, permeation is the idea that the Gospel of Jesus Christ passes into, throughout, or onto our schools and results in palatable change to the school (not just a ‘presence’). Hanging a cross on the wall is a lesser form of permeation compared to, say, building a school in the shape of a cross. Beginning with prayer is not as ‘permeative’ as, say, incorporating the faith into a lesson on geometry; for instance, relating circle geometry and the golden ratio to the number of fish caught in John 21:11.

Intellectual formation enables permeation by providing the teacher with enough knowledge of the faith that they can identify overlap between their subject matter and Church teaching. It’s akin to using a sports analogy to teach physics. A billiard table makes an excellent stage for the play of conservation of momentum, but one needs a familiarity with both billiards and physics to pull it off. If a Catholic teacher is to permeate her subject matter with the faith, she must be familiar with both: (a) the Catholic faith, and (b) her subject matter. For this reason, intellectual formation should be both general (i.e. touching on foundational Christian truths) and subject specific.

After decades of envisioning the faith solely in terms of relationships (to God, Jesus, other people, etc.), shifting the focus of faith formation toward intellectual formation can be met with resistance. Consider, however, that mature relationships require more than mere performative action. We have to actually learn about the people we love; one cannot truly love what one does not know.

Grant Gay is the Director of Catholic Education for Christ the Redeemer Catholic School Division.

- Details

- Written by Dean Sarnecki

- Category: Education Philosophy

“For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” 1 Cor. 1:18

I feel that our lives are like a ship in rough seas, and, though we hold strong to the rudder, the seas toss and turn us endlessly. Just when we feel we are in control, another wave blindsides us and we struggle to regain a sense of direction. For those of us who believe in the power of God, it is that power that maintains our lives, anchors us to something solid, and provides a rudder in stormy seas.