The Three Forms of Permeation

Previously on this blog, I reflected about what it means to say that Catholic schools should be characterized by permeation. (Some, with good reason, prefer the word “integration,” and, if you are one of these people, you can feel free to mentally replace “permeation” with “integration” every time it appears in this post.) I suggested that there are three forms of permeation: Worldview permeation, worship permeation, and witness permeation.

Since writing that post, it has occurred to me that these three forms of permeation roughly correspond to the three offices of Jesus Christ: Prophet, Priest, and King.

- The prophet’s mission was to preach the law of God, to explain to the people of God what that law called on them to do in every aspect of their lives, and to remind them of God’s promises. This corresponds to worldview permeation.

- The priest’s function was to make the sacrificial offerings to God and to officiate over the people’s liturgical celebrations. This corresponds to worship permeation.

- The king’s job was to rule the people in accordance with God’s laws and to execute justice, especially on behalf of the poor and downtrodden. This corresponds to witness permeation.

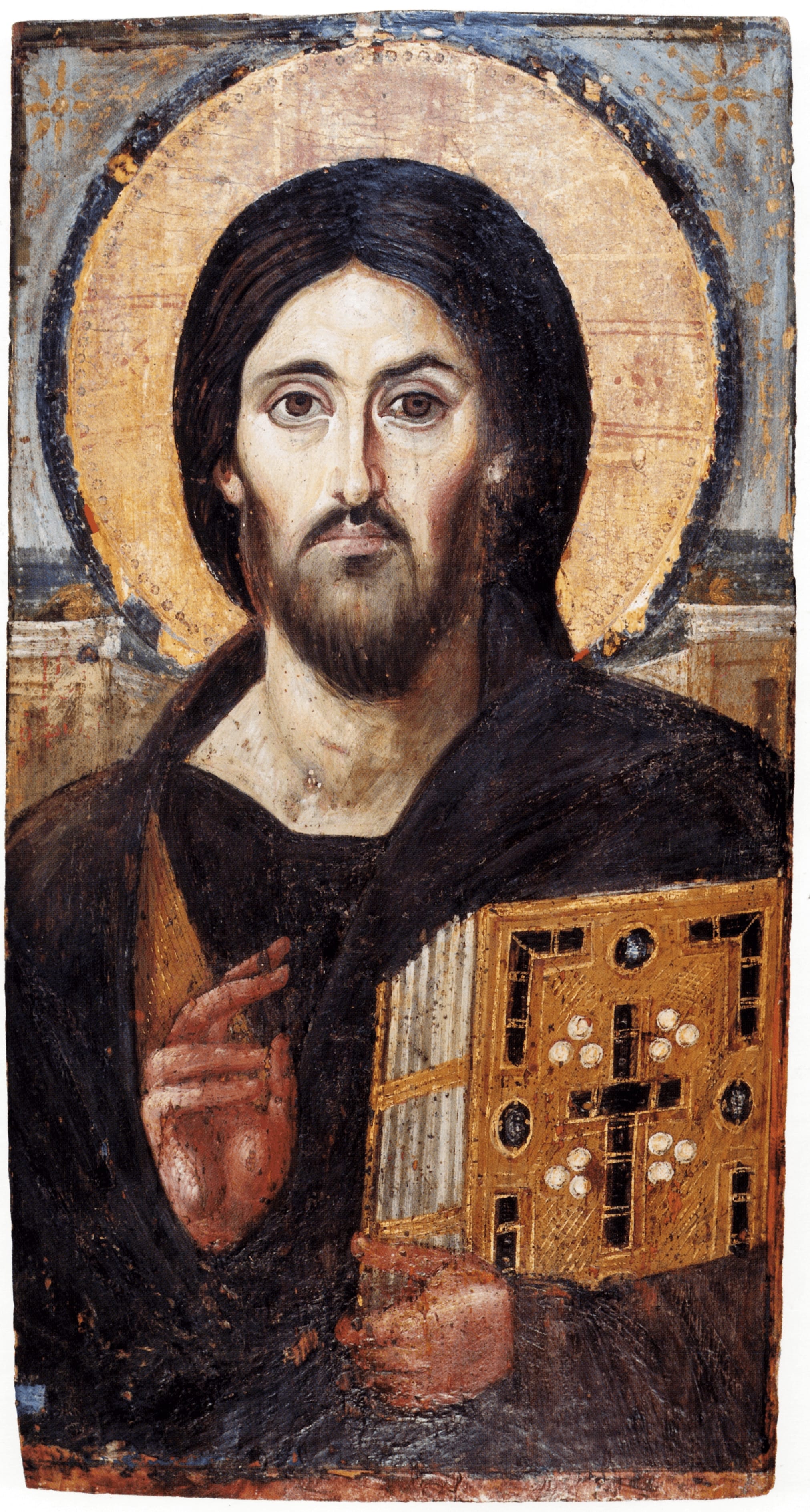

Jesus fulfills all these roles, and permeation is therefore a participation in the ministry of Jesus Christ as applied to the work of education. (This should remind us that permeation is also impossible unless it occurs through Jesus Christ, Who has sent His Spirit to empower us to carry on His mission.)

But the question then arises of who is supposed to do this work. The Magisterium (that is to say, the Church exercising her authority to teach) has consistently stated that the task of permeation in a school falls primarily to its teachers–not to administrators, trustees, parents, students, or support staff (though every one of these groups has an important role to play as well), but to the teachers. Having solid Catholic teachers may not be a sufficient condition for a permeated school (for example, you could have a school full of great Catholic teachers who are stifled by bad policies), but it is a necessary one.

What Kind of Teachers?

The Catholic School Superintendents of Alberta (CCSSA) has recognized this and have produced excellent criteria for identifying the kind of teacher a school needs if permeation is going to take place there. (Remember, permeation is the work of the Holy Spirit, not us, but God works through instruments, and so a principal will want to hire teachers who are able and willing to serve as His instruments.)

One such metric is the Catholic version of the Teaching Quality Standard (TQS), which takes the provincial standards for teacher professionalism and adds various indicators that are particular to Catholic education. For example, the TQS used by public schools lists “Engaging in Career-Long Learning” as a competency teachers should strive for. In addition to the indicators listed in that version, the Catholic TQS includes “[s]eeking personally to grow in his or her spirituality and faith, understanding of Catholic teachings and doctrine” as one of the signs of this competency.

This is helpful, but it is worth remembering that the TQS is a secular set of criteria onto which the Catholic TQS imposes a distinctively Catholic perspective. This is fine, as far as it goes, but one wonders if there is not a criteria for Catholic teachers that starts with the question, “What kind of teacher can God use for permeation?”

One possibility here is found in a helpful CCSSA document called “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” To tease out the criteria for such a teacher, this text essentially works backwards from Archbishop Miller’s five marks of a Catholic school, that is: A Catholic school is (1) grounded in a Christian anthropology, (2) imbued with a Catholic worldview, (3) animated by a faith-infused curriculum, (4) sustained by Gospel witness, and (5) shaped by a spirituality of communion. Based on these, the CCSSA document identifies the “five marks of an excellent Catholic teacher”:

- “An excellent Catholic teacher recognizes that each person has an eternal destiny and is created in the image of God.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher expresses and develops a living Catholic vision of the world.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher permeates faith and wisdom through pedagogy and curricular content.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher witnesses to others a life lived in relationship with Jesus Christ.”

- “An excellent Catholic teacher contributes to a spirituality of communion.”

This is undoubtedly a great list of things a Catholic teacher should do. After all, these are marks of an excellent Catholic teacher. By definition, a mark is something that is visible; it sets what is marked apart for the observer. An alert administrator should be able to observe an excellent Catholic teacher doing all of these things.

At this point, however, the philosophy teacher in me rears his punctilious little head and fussily insists on making two observations.

One of these observations is that there is such a thing as the fallacy of division. This is the logical mistake of assuming that, because something is true of a whole, it must be true of each of the parts of that whole. An example of this fallacy expressed in syllogistic form would be:

- A car is capable of self-propulsion.

- A steering wheel is part of a car.

- Therefore, a steering wheel is capable of self-propulsion.

Obviously, this is an error. The steering wheel, like all the other parts of the car, has a specific function; when all the parts are performing those functions correctly, then the whole car has the power of self-propulsion. This is the principle of emergence: Powers and properties that are not present in the individual parts emerge when they come together as a whole. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” as they say.

I worry that we may be committing the fallacy of division if we reason thusly:

- A permeated Catholic school has five particular marks.

- Teachers are part of permeated Catholic schools.

- Therefore, each teacher will also have those five particular marks.

To put this differently, what makes sense when describing a whole school can be a bit puzzling when applied to a particular teacher. It makes sense to say a school, as an institution, should recognize the supernatural dignity of each student as well as be animated by a faith-based curriculum. On the other hand, for an individual, isn’t recognizing that each person is made in God’s image (the first mark) just an extension of having a living Catholic vision of the world (the second mark)?

In the same vein, couldn’t there be qualities an individual Catholic teacher must possess (such as classroom engagement skills) that can’t be predicated of the whole school? If so, then using the five marks, which apply to the entire institution, to understand the work of a single teacher runs the risk of leaving out qualities which are distinct to a teacher’s work. It is interesting that “The Excellent Catholic Teacher” includes an appendix on the Catholic teacher’s spiritual commitments and pedagogical style, perhaps indicating that the five marks do not adequately cover all the characteristics we should expect to find in a Catholic teacher.

The other observation comes from the Catholic philosophical tradition. As mentioned, these five marks refer to what a Catholic teacher does. But where does that doing come from? The medieval Scholastics, when working out their Christian philosophy of the universe, formulated a rule: operari sequitur esse. Roughly translated, this means that “the actions of a being flow from the nature of that being.” A teacher can only do the kind of actions described in the five marks if they already are a certain kind of person.

To put this another way: You can’t just ask any given teacher to be able to do all these things. A teacher who lacks certain personal and professional qualities won’t be able to permeate faith and wisdom or witness to a life lived in relationship with Jesus Christ, just like a teacher without certain personal traits won’t be able to work in a Suzuki music school or a hockey academy. (Notice: Even if a teacher were a good educator and a fan of hockey, that wouldn’t mean he was suited to teach at a hockey academy. By extension, is a teacher ready for permeation just because she is a good teacher and a devout Catholic?) Before looking at whether a Catholic teacher does these things, we should consider what kind of teachers can do these things.

To that end, I would suggest that, beyond the marks of a Catholic teacher, we should be on the lookout for teachers with certain kinds of traits, personal characteristics that give rise to the actions from which a permeated school emerges.

The Five Traits of a Catholic Teacher

The Church’s Code of Canon Law lays down certain rules about who should be allowed to teach in Catholic schools. Canon 804 §2 declares that religious educators (which really means all teachers in a Catholic school, since all education in a Catholic school has a religious dimension) “are outstanding in correct doctrine, the witness of a Christian life, and teaching skill.” The 1982 Vatican document Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith add two further criteria: Catholic teachers should be able to work in community, which means collaborating with colleagues as well as with parents (para. 34) and “develop in themselves, and cultivate in their students, a keen social awareness and a profound sense of civic and political responsibility” (para. 19).

From these Church documents, then, we gather that a Catholic teacher must possess at least five traits:

- Knowledge of Catholicism

- Christian witness in life

- Pedagogical knowledge

- Skill in collaboration

- Sense of civic responsibility and need to instill this in students

There are two groups of traits here. The first two are unique to Catholic teachers. The last three can also be seen among non-Catholic teachers, but will look different in a Catholic teacher. I call these Permeation-Unique Teacher Traits and Permeation-Infused Teacher Traits, or PUTTs and PITTs. (Of course, you could also call them IUTTs and IITTs.) The PUTTs inform the other three traits and turn them into PITTs.

All teachers should be skilled in pedagogical technique. However, two equally skilled teachers could have two completely different pedagogical strategies. This matters because different pedagogical methods have different philosophies embedded in them, and some of those philosophies are more compatible than others with the Catholic view of reality. To take just one example: In the realm of early childhood education, compare the pure constructivism of the Reggio Emilia method, which developed in non-Catholic schools, to the emphasis on structured play-based learning in a Montessori classroom. This difference is not unrelated to the fact that Maria Montessori was a devout Catholic and therefore had a belief in objective truth that may not be present in the Reggio pedagogical philosophy. This does not mean a Catholic teacher in an early learning classroom must strictly follow Montessori and learn nothing from Reggio, but it does mean she will be aware of whether her pedagogy is in accordance with the Catholic worldview. This third trait is therefore to be understood through the lens of the first trait.

All teachers should have skills in collaboration, but, for a Catholic teacher, this is part of a broader “spirituality of communion,” to go back to the phrase of “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” For her, this will be both an exercise in professionalism as well as a recognition that the work of Catholic education is always ecclesial (that is to say, rooted in the broader community of the Church). The Catholic teacher recognizes that she is part of the body of Christ and plays an important but subservient role in a bigger plan that God is working out in her school community. In collaborating – which often takes great humility – the Catholic teacher testifies by her actions that permeation is ultimately God’s work, not hers. The second trait therefore shapes this fourth one.

All teachers should have skills in collaboration, but, for a Catholic teacher, this is part of a broader “spirituality of communion,” to go back to the phrase of “The Excellent Catholic Teacher.” For her, this will be both an exercise in professionalism as well as a recognition that the work of Catholic education is always ecclesial (that is to say, rooted in the broader community of the Church). The Catholic teacher recognizes that she is part of the body of Christ and plays an important but subservient role in a bigger plan that God is working out in her school community. In collaborating – which often takes great humility – the Catholic teacher testifies by her actions that permeation is ultimately God’s work, not hers. The second trait therefore shapes this fourth one.

Finally, all teachers should be concerned for social justice, but what exactly – for a Catholic teacher – social justice looks like, and how to bring it about, is defined by Catholic Social Teaching as outlined in the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. Her vision of what is wrong with politics and the economy, and the steps we need to take to address those problems, will therefore look (at least a little different) than it does for her counterpart in a secular school. To wit: the secular teacher may not see a connection between contraception and climate change – both symptoms of what Pope Francis calls “the throwaway culture” (para. 22 of Laudato Si) – or between prayer and social activism; a Catholic teacher, however, will perceive these connections and model the inseparability of love for God and love for neighbour to her students. Both the first and the second traits are at play in this fifth one.

A teacher who possesses these five traits, or who is being formed in them and allowing God to develop them in her, is ready to participate in Christ’s prophetic, priestly, and kingly ministry in her work. A school staffed with teachers like her is one where permeation will emerge and the five marks will be visible for all to see.

Brett Fawcett teaches for Elk Island Catholic Schools at the Chesterton Academy of St. Isidore, and is a doctoral student at the University of Calgary.